The past year has seen a wave of revelations about powerful people—nearly all men—perpetrating sexual violence against those beneath them. The #MeToo moment has provided a platform for countless courageous survivors. Yet while some men have been made to face consequences for the harm they have done, we are far from being able to solve the problem of male sexual violence. Focusing on the wrongdoings of specific men tends to exceptionalize them, as if their actions took place in a vacuum. This is consistent with the mechanisms of a criminal justice system focused on individual guilt and a reformist politics premised on the idea that the existing government and market economy would serve us perfectly if only the right people were in power. But with the bad behavior of so many men coming to light, we have to consider the possibility that these are not exceptions at all—that these attacks are the inevitable, systemic result of this social order. Is there a way to treat the cause as well as the symptoms?

Trigger warning for descriptions of sexual violence.

Download a zine version of this article here.

Virtually all recent mainstream coverage has treated sexual harassment and assault as an issue distinct from capitalism and hierarchy. When writers admit that capitalism and hierarchy play some role, they imply that what is harmful about these systems can be fixed through reform. They exhort us to appeal to power to solve the problems power causes: we are to pressure corporations to fire their executives, to use the media to shame media moguls, to use democracy to punish politicians. In short, we are supposed to use the very structures through which our abusers hold power to take it away from them.

On the contrary, we can’t be effective against rampant sexual assault without confronting its root causes.

A tattoo by Charline Bataille inspired by Jenny Holzer.

A Very Brief History of Sexual Assault in the United States

Sexual assault and rape are woven into the very origins of the United States. The original colonists did not consider the indigenous inhabitants worthy of the same moral considerations as white Europeans. Sexual assault and rape were systematically employed as colonial tools. Michele de Cuneo, a nobleman and a shipmate of Columbus, described the following scene in a letter, apparently without shame or remorse:

While I was in the boat I captured a very beautiful Carib woman, whom the said Lord Admiral gave to me, and with whom, having taken her to my cabin, she being naked according to their custom, I conceived desire to take pleasure. I wanted to put my desire into execution but she did not want it and treated me with her finger nails in such a manner that I wished I had never begun. But seeing that (to tell you the end of it all), I took a rope and thrashed her well, for which she raised such unheard of screams that you would not have believed your ears. Finally we came to an agreement in such a manner that I can tell you that she seemed to have been brought up in a school of harlots.

Slaves, too, were routinely sexually assaulted. This was an essential aspect of the system of slavery: in addition to domestic labor, enslaved women were forced to engage in sex and reproduction that served to add more slaves to their captor’s holdings.

Workers have also experienced sexual harassment and assault for as long as there has been a workforce. This is just one of the many manifestations of the unequal power dynamics between employers and employees.

Throughout all this, women were never passive victims. Women have always fought against their abusers with ferocity, creativity, and diversity of tactics. For example, in the mid-1800s, a slave named Harriet Jacobs fought fiercely against her captor; after resisting his sexual advances, she hid in a crawlspace for seven years to avoid him. She eventually escaped to New York and obtained legal freedom. An early forerunner of the #MeToo movement, she wrote letters to the New York Tribune detailing her experiences and in 1860 published Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, one of the first books to detail enslaved women’s experiences of sexual assault.

Starting in the early 1900s, women formed labor unions that fought for the rights of female workers, including the right not to be sexually harassed and assaulted. Black women’s struggles against workplace harassment led to the creation of the first laws against sexual discrimination and harassment. In 1993, Lorena Bobbitt cut off her abusive husband’s penis and threw it in a field after he raped her. A jury acquitted her. These are all legitimate forms of resistance.

“They passed round the bleeding stump, as if they had finally exterminated a wild animal that had been preying on each and every one of them, and saw it there inert and in their power. They bared their teeth, and spat on it.”

-A passage from Emile Zola’s 1885 novel Germinal in which a mob of starving women workers castrate the corpse of a shopkeeper who has been extorting them for sex in exchange for food.

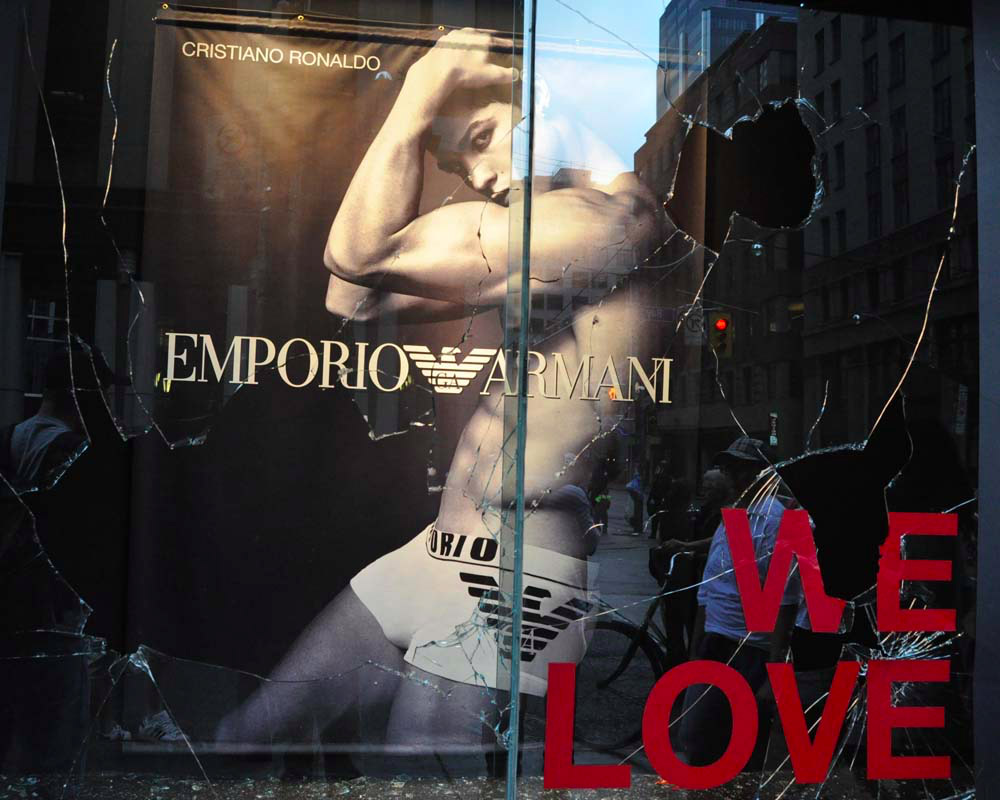

Corporations Won’t Solve This

Of the men whose behavior is finally coming to light, it was no secret that many of them were abusers. Nothing is different now except that corporations have taken a bit more notice. Corporate media outlets have published women’s accounts; some corporations have fired rapists if what they have done is deemed egregious enough. Should we be grateful to corporations for firing serial sexual predators once enough accusations pile up that it becomes a problem for their brand?

These corporations are just plugging the oil leak that finally made the news. But who creates and maintains this pipeline? They do. Let’s not pat them on the back for solving a problem that they caused.

Most of these companies have known about these accusations for years without doing anything. Worse, they’ve allowed these men to rise up the ranks of power to the point that their serial abuse warrants national news attention. In other words, these corporations have facilitated these men’s behavior by giving them additional opportunities with which to harass, assault, and rape women. For every Harvey Weinstein whose actions are finally made public, there is another Harvey Weinstein who gets away with serial assault thanks to the assistance of the institution that gives him power.

Why do corporations have a vested interest in helping rapists succeed in business? While misogyny is partly to blame, we have to look at the bigger picture. Corporate success is determined by how much profit a business produces, not by whether it protects women from sexual assault. In capitalism, whether to oust an assaulter becomes a simple economic equation: how is his presence affecting the bottom line?

Take the case of Bill O’Reilly. Since 2002, Fox News and O’Reilly have paid out many millions of dollars to settle sexual harassment claims. During this time, O’Reilly continued to be a rising star at Fox, negotiating a $25 million a year contract as recently as January 2017. While media coverage and exposés finally forced Fox to fire O’Reilly, Fox knew he was an abuser for more than a decade and shelled out millions to silence women he abused. Fox’s behavior is not so mysterious when one learns that in 2015, O’Reilly’s show earned Fox more than $180 million in advertising.

This is not an anomaly; this is a standard utilitarian calculation that businesses make all the time. Imagine you’re O’Reilly’s conscientious supervisor. Having just discovered O’Reilly’s long history of harassing women, you go to your bosses and demand that they fire O’Reilly. Even if your bosses agree with your demand from a moral standpoint, how could they explain the loss of O’Reilly, the goose who lays the golden eggs, to their shareholders? Capitalism is designed to maximize profit over everything else, including ethics and safety.

This system also makes it difficult to fight back against abusers. In a hyper-competitive market, a single setback can mean the end of your career, your healthcare, your ability to pay rent. The stakes are higher for women and trans people, especially those of color, who are far more likely to experience poverty than men. Those who have gained a footing in the economy may be understandably hesitant to risk losing it, and it’s no secret that those who resist abuse or call out their abusers often face adverse consequences for doing so.

Targets of sexual harassment face impossible choices: do I allow this abuse to continue or risk losing income I desperately need? Do I report this abuse and risk deportation? Do I leave this job without reporting this abuse? If I do, does that mean that others will be preyed upon after me?

Capitalism, the state, and other forms of hierarchy offer sexual predators many ways of doing harm to those who resist them. O’Reilly, Weinstein, Ailes, Farenthold (the list goes on and on and on) all routinely harmed or ended the careers of those who opposed them.

Fears about job security also affect those who are asked to witness or even abet abusers. Weinstein used his employees to make his victims feel a false sense of security before he assaulted them, often asking staffers to come to the beginning of nighttime meetings and then dismissing them so he could be alone with his victims. One former employee described a scene in a nighttime meeting in which Weinstein demanded she tell a model that Weinstein was a good boyfriend, and became enraged when she said she no longer wished to attend these “meetings.” It is easy to feel self-righteous anger at staffers who abetted Weinstein, but it is undeniable that Weinstein’s position of power enabled him to ruin people’s lives. While we deserve for others to be brave in standing up for us even against the most powerful foes, it is unrealistic to think we could put an end to sexual harassment and assault in a system in which people have to martyr themselves in order to protect each other.

Abolishing capitalism and all other systems that concentrate wealth and power into the hands of a few would not put a stop to sexual assault, but it would greatly reduce the coercive economic power that the rich and powerful wield over the rest of us. Without those structural imbalances in power, assaulters would not have the means to manipulate anyone into complicity and silence. This may sound utopian, but it is the only realistic solution if we’re serious about combatting sexual assault. No system that centralizes wealth and power can prevent that power from being used to coerce or harm people.

No, we really don’t.

The Criminal Justice System Won’t Solve This

The law is no friend to victims of sexual harassment and assault. Police officers across the United States have brought charges of false reporting against sexual assault survivors who went to them for help, only to later see these victim’s stories confirmed when their assaulters were identified and convicted. Sexual assault survivors who manage to convince the police not to arrest them for false reporting can find themselves jailed in order to compel their testimony in court.

ICE uses courts as a trap for undocumented people. Undocumented people cannot even enter a courthouse without risking arrest and deportation. In this way, the state systematically facilitates the sexual assault of those whose papers are not in order.

Even if the police don’t throw you in jail, only three to six percent of workplace harassment claims ever make it to trial. Some of these cases are settled, but many are dismissed due to the law’s high bar for what constitutes harassment (the harassment must qualify as “severe” or “pervasive”). In one typical example, a construction worker brought a case against a supervisor who talked about raping him multiple times. The worker’s case was dropped because the supervisor’s actions occurred over a ten-day period and therefore did not meet the standard of being “pervasive.”

The court system not only punishes those who attempt to utilize it—it also targets those who try to defend themselves. In the New Jersey 4 case, a group of black women defended themselves against a catcaller who threatened and attacked them. They were prosecuted and four were sentenced to between 3.5 and 11 years in Rikers.

The idea that the law could ever serve to put an end to sexual harassment and assault is a patriarchal myth. Men have always promised to protect women from other men in return for power over them; this is part of the protection racket that forms the foundation of patriarchy. In fact, the law is integral to maintaining the oppressive hierarchies that create the conditions for a wide variety of power imbalances and grave injustices, including sexual assault.

The criminal justice system exacerbates all the problems we have already seen in the corporate sector. While corporations implicitly hold people hostage in the context of the capitalist economy, the criminal justice system explicitly holds people hostage via the coercive apparatus of the law and the state. It is the epitome of power being distributed to the few and entirely denied to the many, and as such it is a site of terrifying abuses of power. People in prison are routinely sexually assaulted, often by their jailers. When we appeal to the violent authority of the state to punish our abusers, we are complicit in perpetuating the power dynamics that we claim to oppose.

We need to explore systems of justice that hold people accountable to each other, rather than to a higher power. Wherever we concentrate power, we will see abuse.

Viewing Sexual Harassment through an Intersectional Lens

Although we are framing this primarily in gendered terms, the identities “male” and “female” are just proxies with which to discuss different degrees of power and privilege. Whose voices we hear and how we respond to those voices is determined by a myriad of other factors including race, sexual orientation, economic status, ability status, and first language. In seeking to disentangle ourselves from patriarchy, we need to internalize the way our privileges protect us from harm that others face. We need to listen to the stories of those most likely to be harmed under patriarchy and capitalism: black women’s stories, trans people’s stories, undocumented workers’ stories, poor people’s stories.

We need to take note of whose voices those in power seek to discredit. For example, the only sexual assault charges Harvey Weinstein has specifically disputed came from the only black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, who has accused him of harassment or assault.

This Is about Power, not Sex

Although women also perpetrate sexual assault, we are statistically far less likely to do so than men. Is this because women are inherently better, more moral, or less violent than men? If we are, it is in part because we, as non-men, are not taught that we must embody the norms of toxic masculinity that are symptomatic of patriarchy, i.e., that women are objects, or that our self-worth is based on the number of women we fuck. Men’s internalized toxic masculinity accounts for many of the reasons they sexually assault women.

Some have suggested that the solution to rampant sexual harassment and assault is that women should replace men in all positions of power. But the problem is not the condition of maleness; the problem is patriarchy, an unequal distribution of power. As long as some hold power over others, the powerful will prey on the less powerful, regardless of who occupies these roles.

Patriarchy is not the bad behavior of a few specific men, but the framework of relations that fosters it.

So What Do We Do?

To call out sexual predators without seeking to dismantle the system of power that created them is like bailing water out of a sinking ship. The fundamental problem isn’t a shortfall of publicity, law, policy, or education; the fundamental problem is that the systems that purport to keep us safe make us vulnerable.

We have to weave together the ways that we respond to specific instances of sexual harassment and violence with a determination to confront and undermine the social order that gives rise to them. In every case of male violence, we should be clear that we are not dealing with an exception, but with a problem that is a structural feature of our society. At the same time, we need to create models of transformative justice that can replace the criminal justice system without replicating any feature of it, and to foster new ways of relating in which patriarchy, white supremacy, and other forms of authority do not determine the possibilities of our lives. Every person of every gender stands to gain from this.

Let us join hands, teeth bared.

“I’m not your prey, I still have teeth” by kAt Philbin.

Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.

SCUM will not picket, demonstrate, march or strike to attempt to achieve its ends. Such tactics are for nice, genteel ladies who scrupulously take only such action as is guaranteed to be ineffective… If SCUM ever marches, it will be over the President’s stupid, sickening face; if SCUM ever strikes, it will be in the dark with a six-inch blade.

–Valerie Solanas, SCUM Manifesto

Further Reading

The history of sexual assault in the United States:

-

Slavery and the Roots of Sexual Harassment by Adrienne D. Davis

-

Feminism and the Labor Movement: A Century of Collaboration and Conflict by Eileen Boris and Annelise Orleck writing for CUNY’s New Labor Forum

-

Sexual Harassment Law Was Shaped by the Battles of Black Women by Raina Lipsitz writing for The Nation

Alternatives to criminal justice:

-

Sexual Assault Resources from North East Anarchist Network (particularly the Accountability Processes section)

-

Revolution and Restorative Justice: An Anarchist Perspective by Peter Kletsan writing for Abolition Journal

-

Accounting for Ourselves: Breaking the Impasse Around Assault and Abuse in Anarchist Scenes from CrimethInc.

Sexual assault and neoliberalism:

-

Profiting from Rape: Sexual Violence and the Capitalist State by Kelly Rose Pflug-Back writing for The Feminist Wire

-

The Consent of the Ungoverned by Laurie Penny writing for LongReads

Sexual assault on the margins:

-

Cultivating Fear: The Vulnerability of Immigrant Farmworkers in the US to Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment by Grace Meng published in Human Rights Watch

-

Sexual Assault When You’re on the Margins: Can We All Say #MeToo? by Collier Meyerson writing for The Nation